Freelist Memory Buffer Allocator

July 2, 2025

In modern computer systems, memory is one of the most precious and constrained resources — a limitation that’s especially pronounced in the era of artificial intelligence. In the domain of on-device training, memory bottleneck have become one of the hardest obstacle to overcome; neural networks are notoriously memory hungry, especially during backpropagation, which involves storing and manipulating large amounts of intermediate data. Devices with 8GB RAM often struggle to survive, and the situation is even more dire for smaller, resource-constrained hardware.

Therefore, it is necessary to make good use of every chunk of memory. However, naive methods leave us with severe memory fragmentation problems. For example, consider a process that allocates and then frees a series of small memory chunks that don’t align cleanly to page boundaries. The virtual memory pages may remain partially used, preventing the kernel from reclaiming or reusing them. Worse yet, if allocations are made across many scattered pages, the working set grows, leading to more page faults and cache misses. This means that even though you have plenty of total free memory in theory, in practice, much of it is locked in unusable fragments, ultimately leading to inefficient memory use and potential out-of-memory errors.

To overcome memory fragmentation, many programs implement their own free list–based allocators. One of the most common is the power-of-2 free list allocator.

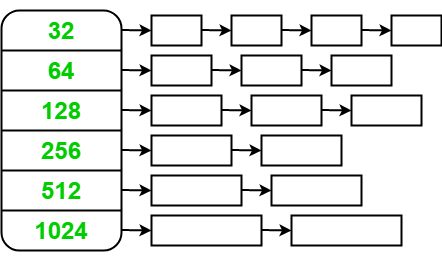

The structure can be abstracted as a map, where each key represents a respective block size, such as 128B, 256B, 1kB, etc., and each value is a pointer to a linked list to memory buffers. Each buffer in the list is preallocated with the corresponding size. Each memory block has a header, which typically stores the pointer to the next available memory block (if in free list), or the pointer to the free list which it was allocated from (if allocated); in some applications, headers are used to store the size of the memory block. This leads to a slight reduce of usable memory size.

When user calls malloc, they provide the number of bytes they wish to allocate. The memory allocator then computes the smallest predefined block size that can accommodate the requested memory plus the header. For instance, if the user requests 29 bytes and the header is 4 bytes, the allocator rounds up and selects the 64-byte block. It locates the corresponding free list for 64B blocks, pops the first buffer from that list, and returns a pointer to the usable memory region.

When user calls free, they provide the pointer to the allocated block. The allocator uses this pointer to access the block’s header, which contains a pointer to the linked list (or a block size, which allocator can use to compute which free list the block belongs to). The block is then safely returned to the linked list, making it available for further allocation

If a list of a particular size is empty, the allocator will typically do the following:

- Block the request, wait until a block is returned

- Allocate a larger block instead of the best-fit

- Request more memory from system level paging

Although this method solves the memory fragmentation problem to some extent, it is far from perfect. Fragmentation still occurs, particularly for larger block sizes, where freed blocks may remain unused if future allocations don’t match their size class. Additionally, there’s no interchangeability between block sizes — a 64B block cannot be repurposed to satisfy a 32B request, even if no 32B blocks are available. This rigid separation can lead to underutilized memory pools. Furthermore, maintaining multiple free lists increases allocator complexity and metadata overhead. In worst-case scenarios, the system may still run out of memory despite having plenty of unused blocks scattered across different size classes.